If you, like me, follow lots of meme-heavy social media accounts, you’ve probably come across versions of the following posts: A meme depicting a tangled mess of string labeled “my anxiety,” and next to it, that same mess adorned with holiday lights, labeled “my festive, holiday anxiety.” A tweet about depression that reads “This too shall pass. And then come back again. But worse this time.” A post that says “My therapist told me to go on vacation. Now I just have tropical depression.”

They’re funny, light-hearted, maybe even a little mood boost if we feel we can relate. We chuckle and move onto the next post.

So, what’s the problem?

Not the memes! Anything but the memes!

We’ve talked about the pros and cons of social media mental health content before—about the surprising risks of mental health awareness,1 and the problems with self-diagnosis online.

But a new study in the Journal of Clinical Psychology2 suggests a subtler risk to mental health content:

A “fixed mindset.”

Tell me more…

We know that many people do not get the treatment they need for mental health concerns. There are many larger, systemic reasons for this, but one factor that can contribute is people’s beliefs about mental illness. If a person believes that concerns like depression and anxiety are unlikely to get better, that there’s nothing they can do to improve symptoms, and that treatment will be ineffective, they’re less likely to seek out treatment.

These beliefs—that mental illness is intractable, unchangeable, and untreatable—represent a “fixed mindset” about mental illness.

The alternative? A “growth mindset” about mental illness: one that sees these conditions as malleable, treatable, and responsive to treatment and other efforts to improve symptoms.3

Enter: social media, where posts (and memes) can convey any number of messages about mental health, and in doing so, likely shape people’s mindsets.

What did the researchers do?

A team of psychologists at Ohio State University4 recruited 322 college students for an online experimental study. The students were given four minutes to view a series of tweets “at their own pace.” These tweets were selected by the researchers.

The students were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. Depending on the condition, they were shown different types of tweets:

Condition 1: Fixed Mindset. Students saw tweets that “portrayed mental health as a stable condition that does not change.” For example, they saw posts like those described above, insinuating that anxiety never goes away or that depression does not get better, no matter what we do. According to the researchers, these tweets tended to be more “humorous and negative.”

Condition 2: Growth Mindset. Students saw tweets that “emphasized the fluid nature of mental health and the ability to recover from and take control of mental illness.” For example, a caption reading “I got this,” accompanying a meme that said “telling those anxious thoughts who’s really in control.” These tweets tended to be more “uplifting” (i.e., positive and happy).”

Condition 3: Control condition. Students saw tweets unrelated to mental health, but that were generally upbeat and and optimistic (e.g., a post about feeling proud after going for a run).

And what did they find?

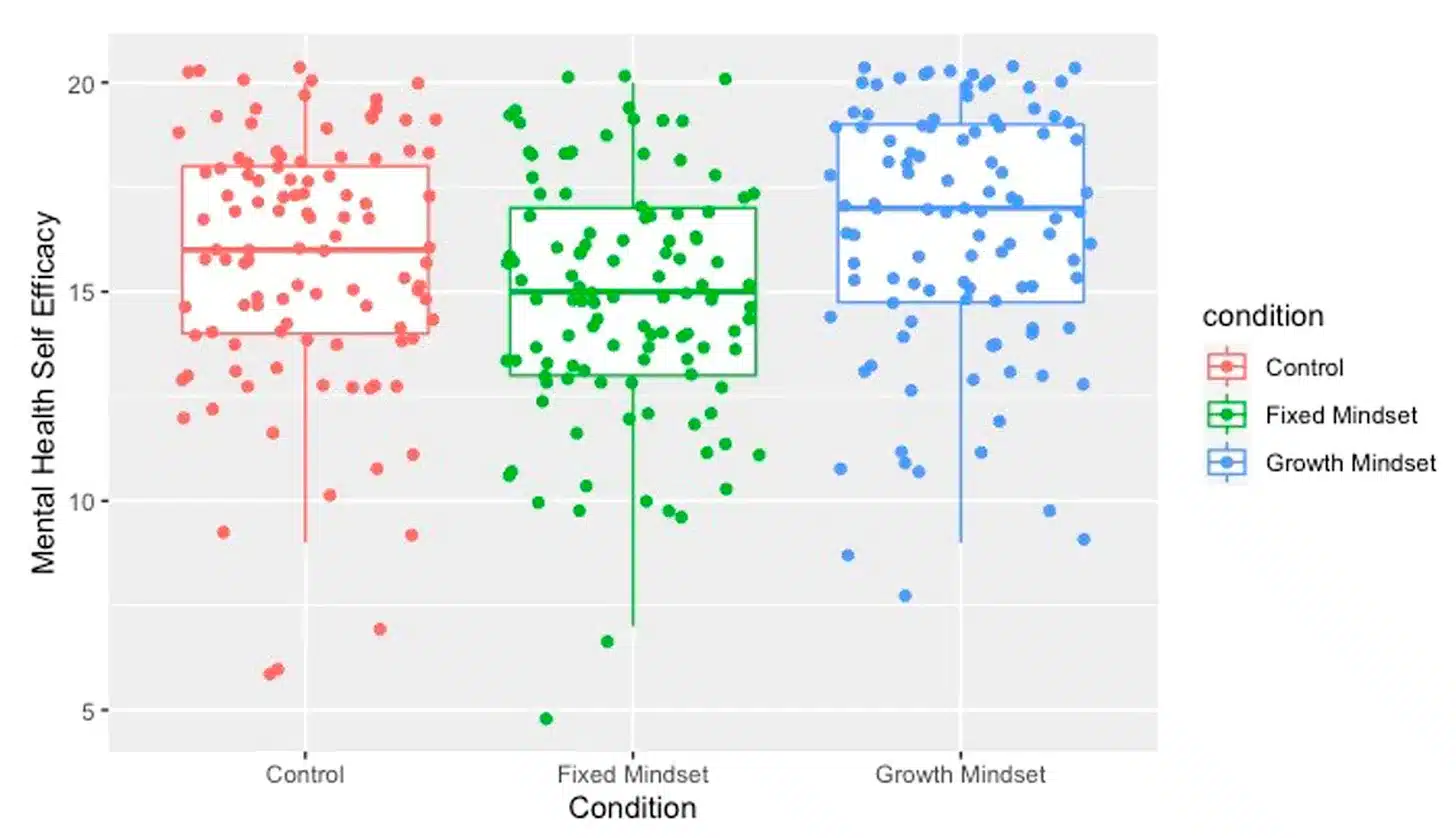

The most important finding of the study was around mental health self-efficacy, or the belief that there are things people can do to help themselves recover from or improve symptoms of mental illness. After viewing the tweets, participants in the “Growth mindset” condition reported higher mental health self-efficacy, compared to participants in the “fixed mindset” condition.

Interestingly, those in the “growth mindset” condition also reported higher mental health self-efficacy than in the control condition, but this effect was not statistically significant. In other words, when they viewed “growth mindset” tweets, participants were no worse (or better!) off than viewing tweets that were totally unrelated to mental health. But those in the “fixed mindset” condition showed lower self-efficacy than those in the control condition—they would have been better off if they’d just seen tweets unrelated to mental health altogether.

Okay, you might say, but weren’t the “fixed mindset” tweets at least more relatable for participants? Didn’t they at least get the benefit of those funny memes? Nope. Participants in the “growth mindset” condition actually rated those tweets as more relatable than those in the “fixed mindset” condition.

In sum: even a brief, four-minute exposure to seemingly light-hearted “fixed mindset” social media posts negatively influenced participants’ beliefs about mental illness.

Now, imagine you’re a teen (or adult) spending hours on social media everyday. And imagine the algorithms-that-be have determined you’re interested in humorous mental health-related content. You can see the problem here.

Every party has a pooper

I love a good meme5 as much as the next person,6 and—as you may have gathered from Techno Sapiens—I’m a strong believer in the power of humor,7 even in the context of mental health challenges. I also really hate to be the one to rain on the mental-health-meme-parade.

That said, these results should make us think twice about the types of “mental health content” that are helpful versus harmful on social media.

There are the blatantly harmful types, of course. The posts that glorify self-harm or disordered eating behavior. The misinformation about depression and anxiety. The posts that encourage self-diagnosis.

But there may be less obvious ones, too, like the ones we see in this study. The ones that subtly shape our beliefs about mental illness, making us feel there’s nothing we can do to make things better, and, over time, making it less likely that we’ll get the help we need.

Of course, this is only one study. There are many questions that are still unanswered. Where do we draw the line between uplifting, relatable humor, and problematic mental health messaging? Would these findings hold true in a different population—like one with existing mental health concerns? If we’re aware of the potential for this content to impact our beliefs, can we protect ourselves against potential negative effects?

Ultimately, though, this study should begin to sow a seed of doubt: we often assume that any “mental health awareness” is a good thing, and that as long as the content isn’t actively harmful, surely it must be helpful. This study suggests otherwise. When it comes to mental health, we need to be careful about the messages we spread. The line between helpful and harmful can be subtle, and we have a ways to go to figure out exactly where to draw it.

Keep Reading

Want more? Here are some other blog posts you might be interested in.